Full HTML

Risk Factors Associated with Preterm Birth of Women who gave Birth in Abia State University Teaching Hospital, Aba, Southeast, Nigeria

Edmund O. Ezirim1, Emmanuel M. Akwuruoha1, Christian O. Onyemereze2, Emmanuel O. Ewenyi3, Isaiah O. Abali4, Augustine I. Airaodion5

Author Affiliation

1 Consultant, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Abia State University Teaching Hospital, Aba, Nigeria

2 Senior Registrar, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Abia State University Teaching Hospital, Aba, Nigeria

3 PhD Student, School of Public Health, University of Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria

4 Consultant Orthopedic Surgeon, Abia State University Teaching Hospital, Aba, Nigeria

5 Lecturer, Department of Biochemistry, Lead City University, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria

Abstract

Background: Preterm birth remains a leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality worldwide. Identifying its risk factors is essential for developing targeted interventions to improve maternal and neonatal health. This study investigated the sociodemographic, obstetric, medical, and lifestyle risk factors associated with preterm birth among women who delivered at Abia State University Teaching Hospital (ABSUTH), Aba, Southeast Nigeria.

Methods: A hospital-based case-control study was conducted at ABSUTH. The study population comprised all the women who gave birth at the facility who met the criteria. Data were collected through structured interviewer-administered questionnaires and medical record reviews. Key variables included maternal age, education level, socioeconomic status, obstetric history, medical conditions, lifestyle factors, and antenatal care utilization. Descriptive statistics, chi-square tests, t-tests, and logistic regression were performed using SPSS version 25, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

Results: A total of 9125 deliveries were recorded during the period of this study, including 1,962 cases (preterm births, <37 weeks gestation) and 7,163 controls (term births, ≥37 weeks gestation). Chi-square analysis showed significant associations between preterm birth and maternal age (p < 0.05), low education level (p < 0.001), low socioeconomic status (p = 0.0351), previous preterm birth (p < 0.001), short pregnancy interval (p < 0.001), hypertension (p < 0.001), diabetes (p < 0.001), infections (p < 0.001), smoking (p < 0.001), alcohol consumption (p < 0.001), and inadequate antenatal visits (p < 0.001). Logistic regression confirmed that hypertension, diabetes, infections, previous preterm birth, and inadequate antenatal visits were independent predictors of preterm birth.

Conclusion: The findings highlight the multifactorial nature of preterm birth, with medical conditions, lifestyle behaviors, and inadequate antenatal care playing crucial roles. Early identification and management of these risk factors through improved maternal health services and health education may reduce the burden of preterm birth in the study setting.

DOI: 10.63475/yjm.v4i1.0010

Keywords: Preterm birth, maternal health, antenatal care, obstetric history, lifestyle behaviors

Pages: 128-133

View: 11

Download: 19

DOI URL: https://doi.org/10.63475/yjm.v4i1.0010

Publish Date: 22-05-2025

Full Text

Preterm birth (PTB), defined as birth before 37 completed weeks of gestation, remains a major public health concern worldwide, contributing significantly to neonatal morbidity and mortality. [1] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 13.4 million babies were born preterm in 2020, accounting for over 10% of live births globally. [2] The burden is disproportionately higher in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where healthcare access, maternal nutrition, and socioeconomic disparities exacerbate the risks associated with PTB. [3] Nigeria, as the most populous country in Africa, has one of the highest rates of PTB, with an estimated incidence of 12%–15%, placing immense pressure on healthcare facilities and neonatal care services. [4]

The etiology of PTB is multifactorial, involving genetic, biological, environmental, and sociodemographic determinants. Established maternal risk factors include infections (e.g., bacterial vaginosis, urinary tract infections), hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (e.g., preeclampsia), gestational diabetes mellitus, poor nutritional status, and previous history of PTB. [5] Socioeconomic and environmental factors, such as poverty, low educational attainment, inadequate prenatal care, exposure to environmental pollutants, and psychosocial stress, also play significant roles. [6] Furthermore, behavioral and lifestyle factors, including smoking, alcohol use, and high physical workload, have been linked to increased PTB risk. [7] While many of these risk factors have been extensively studied in high-income countries, their relevance and interplay in Nigerian settings, particularly in Southeast Nigeria, remain inadequately explored. Hospital-based studies have been instrumental in identifying and evaluating PTB risk factors, providing valuable insights for targeted interventions. [8] However, in Nigeria, much of the existing research is focused on urban tertiary centers, with limited data from Southeast Nigeria. The Abia State University Teaching Hospital (ABSUTH), a major referral center in Aba, serves a diverse population, making it a suitable setting for understanding the local epidemiology of PTB. Given the high burden of PTB and its devastating consequences, including neonatal deaths and long-term developmental disabilities, there is an urgent need to identify and address its risk factors in this region.

This study aims to investigate the risk factors associated with PTB among women who gave birth at ABSUTH, Aba, Southeast Nigeria. Utilizing a hospital-based case-control design, the research will assess maternal sociodemographic, clinical, obstetric, and lifestyle factors contributing to PTB. Findings from this study will inform evidence-based interventions to mitigate PTB risk, improve maternal and neonatal health outcomes, and strengthen healthcare policies in Nigeria.

Study Design

The study was conducted as a hospital-based case-control study to investigate the risk factors associated with preterm birth among women who gave birth at Abia State University Teaching Hospital (ABSUTH), Aba, Southeast Nigeria. To identify significant risk factors associated with preterm delivery, the study design was selected to compare women who experienced preterm births (cases) with those who had term births (controls). The study was carried out for a period of two years, between June 2022 and June 2024.

Study Area

The research was conducted at ABSUTH, a tertiary healthcare facility in Aba, Abia State, Nigeria. The hospital serves as a referral center for obstetric and gynecological cases within the region, providing specialized maternal and neonatal care. It caters to a diverse population, including urban and rural residents, making it a suitable setting for studying preterm birth risk factors.

Study Population

The study population consisted of women who delivered at ABSUTH within the study period. Participants were categorized into two groups:

Cases: Women who experienced preterm births, defined as delivery before 37 completed weeks of gestation.

Controls: Women who had term births, defined as delivery at or beyond 37 completed weeks of gestation.

All participants were required to meet specific inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure the validity of the study.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Women were eligible for inclusion if they had a singleton live birth at ABSUTH during the study period and had complete medical records. Women with multiple pregnancies, congenital fetal anomalies, or incomplete medical records were excluded.

Data Collection and Data Analysis Methods

All pregnant women who delivered at ABSUTH during the study period were included. Data were collected using structured interviewer-administered questionnaires and medical record reviews. The questionnaire was adapted from validated instruments used in maternal and child health research.

Data were entered and analyzed using SPSS version 25. Descriptive statistics, including means, frequencies, and percentages, were used to summarize categorical and continuous variables. Chi-square tests and t-tests were employed to compare characteristics between cases and controls. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine the strength of the association between risk factors and preterm birth, adjusting for potential confounders. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Ethical Considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before data collection. Confidentiality of participant information was ensured by assigning unique identification numbers instead of names. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without consequences.

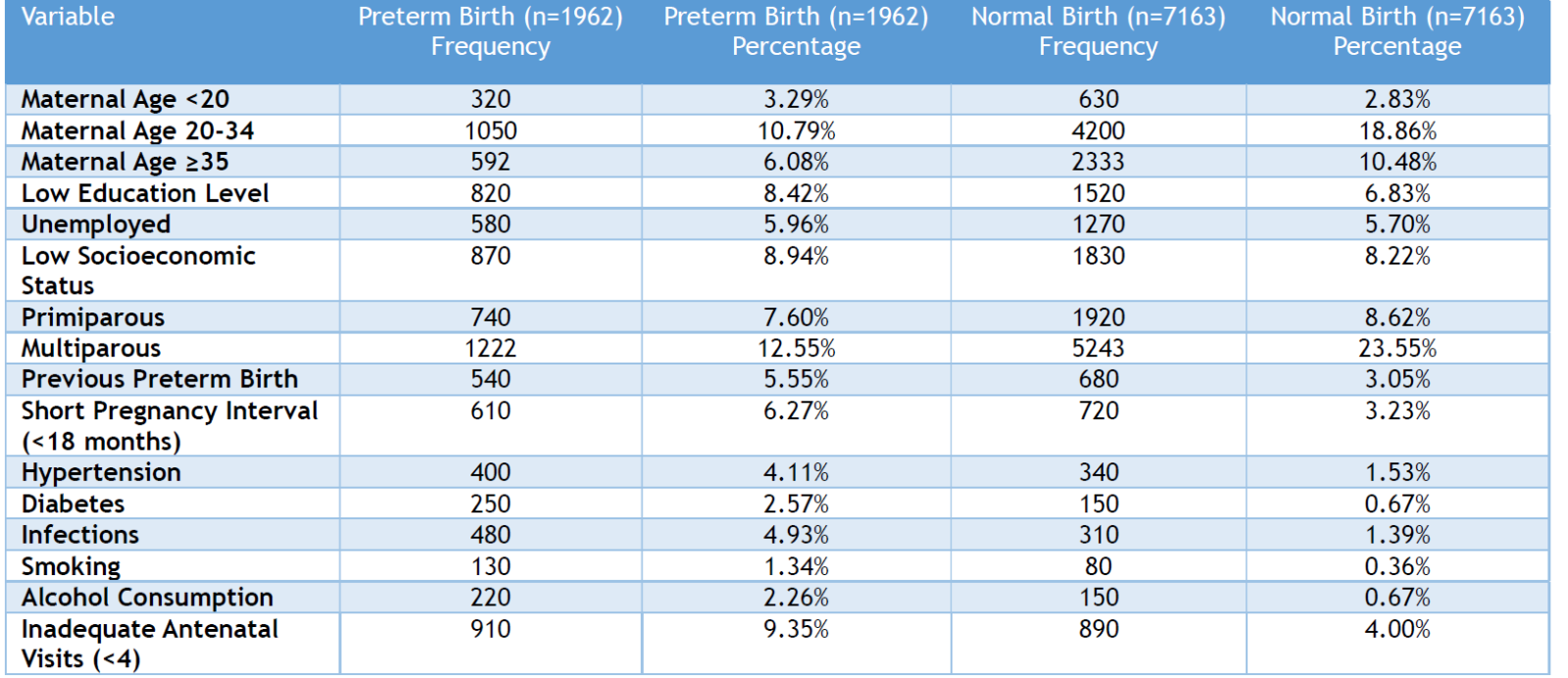

A total of 9125 deliveries were recorded in ABSUTH during the period of this study, including 1,962 cases (preterm births, <37 weeks gestation) and 7,163 controls (term births, ≥37 weeks gestation). Women with preterm births had a higher prevalence of risk factors such as low education (8.42% vs. 6.83%), low socioeconomic status (8.94% vs. 8.22%), and previous preterm birth (5.55% vs. 3.05%). Medical conditions such as hypertension (4.11% vs. 1.53%), diabetes (2.57% vs. 0.67%), and infections (4.93% vs. 1.39%) were also more frequent among preterm births. Additionally, lifestyle factors like smoking (1.34% vs. 0.36%) and alcohol consumption (2.26% vs. 0.67%) were more common in the preterm group. A significant proportion of women with preterm births had inadequate antenatal care (<4 visits) compared to those with normal births (9.35% vs. 4.00%) (Table 1).

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics (Categorical Variables)

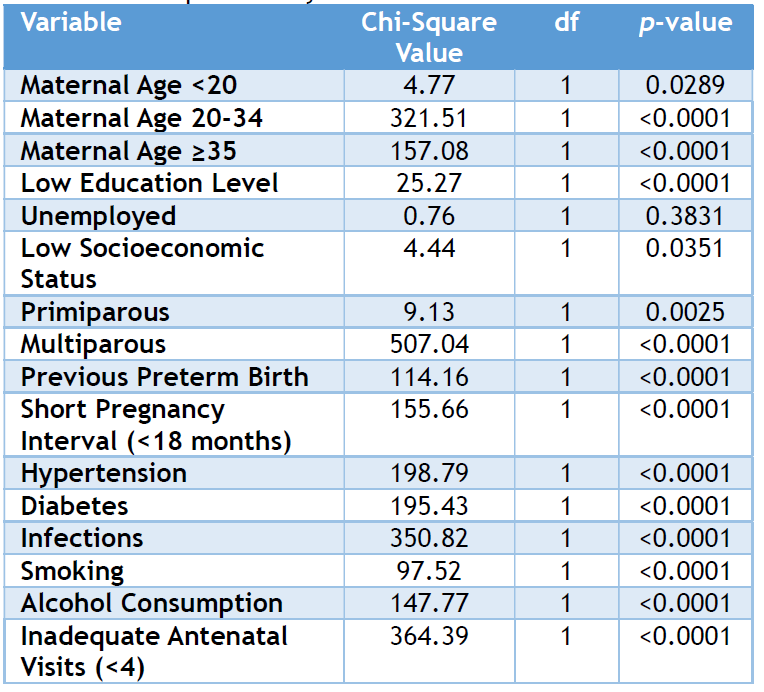

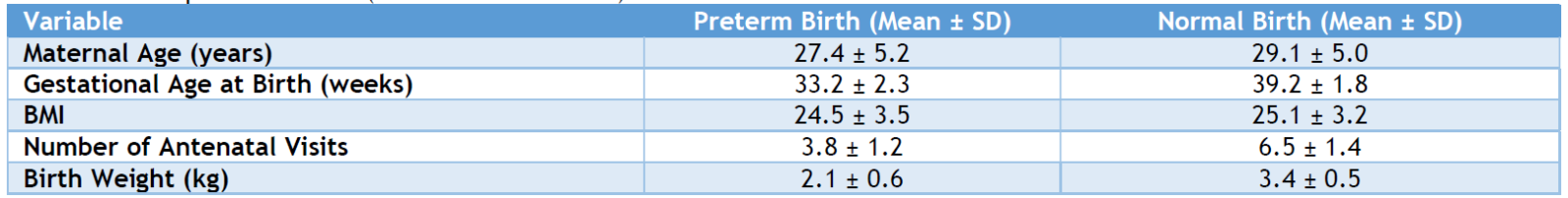

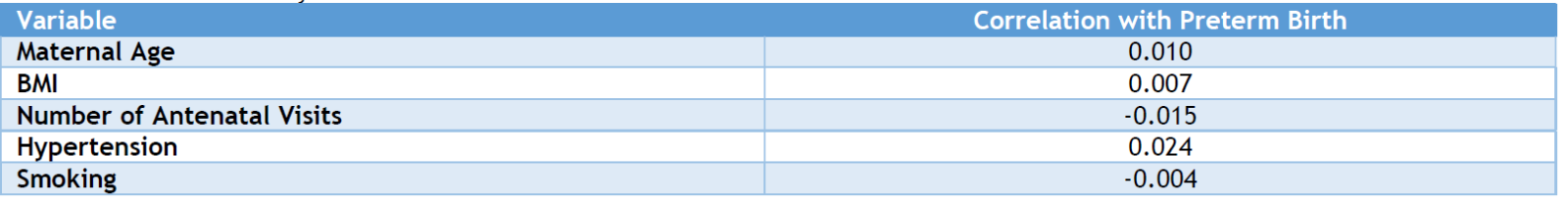

Significant associations (p<0.05) were found for maternal age, education, socioeconomic status, parity, previous preterm birth, short pregnancy interval, hypertension, diabetes, infections, smoking, alcohol consumption, and inadequate antenatal visits. However, unemployment was not significantly associated with preterm birth (p=0.3831) (Table 2). Women with preterm births had a lower mean maternal age (27.4 ± 5.2 years) than those with normal births (29.1 ± 5.0 years). The mean gestational age at birth was significantly lower in preterm births (33.2 ± 2.3 weeks vs. 39.2 ± 1.8 weeks), and birth weight was also lower (2.1 ± 0.6 kg vs. 3.4 ± 0.5 kg). Women who had preterm births attended fewer antenatal visits (3.8 ± 1.2) compared to those with normal births (6.5 ± 1.4) (Table 3). Hypertension (r = 0.024) showed a weak positive correlation with preterm birth, while the number of antenatal visits had a slight negative correlation (r = -0.015). Maternal age and BMI had minimal correlation with preterm birth (Table 4).

Table 2: Chi-Square Analysis

Table 3: Descriptive Statistics (Continuous Variables)

Table 4: Correlation Analysis

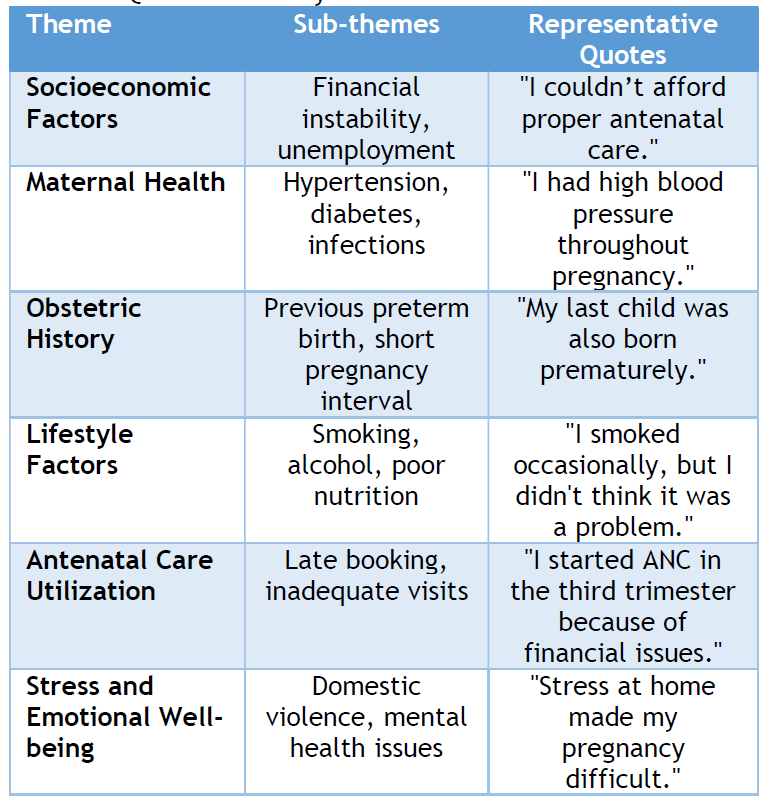

Socioeconomic constraints, maternal health conditions, obstetric history, and lifestyle factors were recurrent concerns. Women cited financial instability as a barrier to antenatal care, while hypertension, diabetes, and previous preterm births were commonly mentioned health-related risk factors. Lifestyle choices such as smoking and alcohol use were also noted. Emotional stress, including domestic violence and mental health struggles, was reported as a contributing factor to preterm birth (Table 5).

Table 5: Qualitative Analysis

Preterm birth, defined as delivery before 37 weeks of gestation, remains a significant contributor to neonatal morbidity and mortality globally. In Nigeria, the prevalence of preterm births poses substantial challenges to maternal and child health [9]. This study, conducted at Abia State University Teaching Hospital, Aba, Southeast Nigeria, examines the risk factors associated with preterm births by analyzing various maternal characteristics and their correlation with preterm deliveries.

The study reveals that maternal age influences preterm birth rates. Mothers under 20 years accounted for 3.29% of preterm births, while those aged 20-34 years represented 10.79%, and mothers aged 35 and above constituted 6.08%. The chi-square analysis indicates significant associations for maternal age groups under 20 (p=0.0289), 20-34 (p<0.0001), and 35 and above (p<0.0001). These findings align with previous research indicating that both younger and advanced maternal ages are risk factors for preterm birth. For instance, a study in Lagos, Nigeria, identified extremes of maternal age as significant contributors to preterm deliveries [10].

Low education levels and low socioeconomic status were prevalent among mothers who experienced preterm births, with percentages of 8.42% and 8.94%, respectively. Both factors showed significant associations with preterm birth (p<0.0001 for low education; p=0.0351 for low socioeconomic status). These results are consistent with studies indicating that limited education and financial instability are linked to higher rates of preterm births. A scoping review in Sub-Saharan Africa highlighted socioeconomic disparities as critical determinants of preterm birth. [11]

Unemployment was observed in 5.96% of mothers who had preterm births, compared to 5.70% in those with normal deliveries. The association between unemployment and preterm birth was not statistically significant (p=0.3831). This suggests that while employment status may influence maternal health, it may not be a direct predictor of preterm birth in this population. [10,11]

Multiparity was more common among mothers with preterm births (12.55%) than those with normal births (23.55%), with a significant association (p<0.0001). Additionally, a history of previous preterm birth and short pregnancy intervals (<18 months) were significantly associated with preterm deliveries (p<0.0001 for both). These findings are corroborated by studies in Nigeria and Ethiopia, which identified previous preterm births and short inter-pregnancy intervals as significant risk factors. [12]

Hypertension and diabetes were present in 4.11% and 2.57% of mothers with preterm births, respectively, both showing strong associations with preterm delivery (p<0.0001 for both). Infections were also significantly associated with preterm births (p<0.0001). These results are in line with previous research indicating that maternal medical conditions such as hypertension and infections increase the risk of preterm birth. [13] Smoking and alcohol consumption were reported by 1.34% and 2.26% of mothers with preterm births, respectively, both showing significant associations (p<0.0001 for both).

These findings align with studies demonstrating that maternal smoking and alcohol intake are risk factors for preterm delivery. [14]

Inadequate antenatal visits (<4) were reported by 9.35% of mothers who had preterm births, significantly higher than the 4.00% in the normal birth group (p<0.0001). This underscores the importance of adequate antenatal care in preventing preterm deliveries. Similar conclusions were drawn in studies conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa, highlighting inadequate antenatal care as a modifiable risk factor for preterm birth. [15,16]

Mothers who had preterm births had a mean maternal age of 27.4 years, gestational age at birth of 33.2 weeks, BMI of 24.5, and an average of 3.8 antenatal visits. In contrast, mothers with normal births had a mean age of 29.1 years, gestational age of 39.2 weeks, BMI of 25.1, and 6.5 antenatal visits on average. These differences highlight the impact of maternal age, gestational age, BMI, and antenatal care frequency on birth outcomes. [17]

The correlation analysis revealed weak associations between preterm birth and factors such as maternal age (0.010), BMI (0.007), number of antenatal visits (-0.015), hypertension (0.024), and smoking (-0.004). These weak correlations suggest that while these factors are associated with preterm birth, they may not be strong individual predictors. [14,16]

Qualitative responses highlighted themes such as financial instability, maternal health issues (e.g., hypertension), obstetric history, lifestyle factors, inadequate antenatal care, and stress as contributors to preterm birth. These insights provide a deeper understanding of the multifaceted challenges faced by pregnant women, emphasizing the need for comprehensive interventions [18-20].

Limitations of the Study

This study has some limitations. Firstly, its cross-sectional nature limits causal inference between identified risk factors and preterm birth. Secondly, the reliance on hospital-based data may introduce selection bias, as it excludes women who delivered at home or in private health facilities. Additionally, some responses may be subject to recall bias, particularly those related to lifestyle behaviors or last menstrual period dates.

The study identifies several significant risk factors associated with preterm births at Abia State University Teaching Hospital, including maternal age extremes, low education, and socioeconomic status, multiparity, previous preterm births, short inter-pregnancy intervals, medical conditions, lifestyle factors, and inadequate antenatal care. These findings are consistent with previous studies in Nigeria and Sub-Saharan Africa, underscoring the need for targeted interventions to address these modifiable risk factors and improve maternal and neonatal health outcomes.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

Each author has made a substantial contribution to the present work in one or more areas including conception, study design, conduct, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. All authors have given final approval of the version to be published, agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

SOURCE OF FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

References

- Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, Chou D, Moller AB, Narwal R, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet. 2012;379(9832):2162–72.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Preterm birth: Key facts [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth

- Ohuma EO, Moller AB, Bradley E, Chakwera S, Hussain-Alkhateeb L, Lewin A, et al. National, regional, and global estimates of preterm birth in 2020, with trends from 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2023;402(10409):1261–71.

- Requião-Moura LR, Viana LA, Cristelli MP, Garcia VD, Esmeraldo M, Filho MA, et al. High mortality among kidney transplant recipients diagnosed with coronavirus disease 2019: Results from the Brazilian multicenter cohort study. PLoS One. 2021;16(7):e0254822. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0254822.

- Fajolu IB, Dedeke IOF, Oluwasola TA, Oyeneyin L, Imam Z, Ogundare E, et al. Determinants and outcomes of preterm births in Nigerian tertiary facilities. BJOG. 2024;131 Suppl 3:30–41.

- Zhurabekova G, Oralkhan Z, Balmagambetova A, Berdalinova A, Sarsenova M, Karimsakova B, et al. Socioeconomic determinants of preterm birth: a prospective multicenter hospital-based cohort study among a sample of Kazakhstan. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2024;24(1):769.

- Alamneh TS, Teshale AB, Worku MG. Preterm birth and its associated factors among reproductive-aged women in sub-Saharan Africa: evidence from the recent demographic and health surveys of sub-Saharan African countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:770.

- Abadiga M, Wakuma B, Oluma A, Fekadu G, Hiko N, Mosisa G. Determinants of preterm birth among women delivered in public hospitals of Western Ethiopia, 2020: Unmatched case-control study. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0245825.

- Akwuruoha EM, Ezirim EO, Onyemereze CO, Ewenyi EO, Abali IO, Airaodion AI. Prevalence and awareness of preterm birth among women who gave birth in Abia State University Teaching Hospital, Aba, Southeast, Nigeria. Int J Stud Midwifery Womens Health. 2025;6(2).

- Butali A, Ezeaka C, Ekhaguere O, Weathers N, Ladd J, Fajolu I, et al. Characteristics and risk factors of preterm births in a tertiary center in Lagos, Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;24:1.

- Mabrouk A, Abubakar A, Too EK, Chongwo E, Adetifa IM. A scoping review of preterm births in sub-Saharan Africa: burden, risk factors and outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;19(17):10537.

- Sendeku FW, Beyene FY, Tesfu AA, Bante SA, Azeze GG. Preterm birth and its associated factors in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Afr Health Sci. 2021;21(3):1321–33.

- Sutherland MR, Bertagnolli M, Lukaszewski M-A, Huyard F, Yzydorczyk C, Luu TM, et al. Preterm birth and hypertension risk: the oxidative stress paradigm. Hypertension. 2014;63(1).

- Ikehara S, Kimura T, Kakigano A, Sato T, Iso H, Japan Environment Children's Study Group. Association between maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy and risk of preterm delivery: the Japan Environment and Children's Study. BJOG. 2019;126(12):1448–54.

- Alamneh TS, Teshale AB, Worku MG, Tessema ZT, Yeshaw Y, Tesema GA, et al. Preterm birth and its associated factors among reproductive-aged women in sub-Saharan Africa: evidence from the recent demographic and health surveys of sub-Saharan African countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:770.

- Alliance for Maternal and Newborn Health Improvement (AMANHI) GA Study Group. Population-based rates, risk factors and consequences of preterm births in South-Asia and sub-Saharan Africa: a multi-country prospective cohort study. J Glob Health. 2022;12:04011.

- Ayele TB, Moyehodie YA. Prevalence of preterm birth and associated factors among mothers who gave birth in public hospitals of East Gojjam zone, Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23:204.

- Penman SV, Beatson RM, Walker EH, Goldfeld S, Molloy CS. Barriers to accessing and receiving antenatal care: findings from interviews with Australian women experiencing disadvantage. J Adv Nurs. 2023;79(12):4672–86.

- Alizadeh-Dibazari Z, Abbasalizadeh F, Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi S, Jahanfar S, Mirghafourvand M. Childbirth preparation and its facilitating and inhibiting factors from the perspectives of pregnant and postpartum women in Tabriz-Iran: a qualitative study. Reprod Health. 2024;21:106.

- Agarwal R, Agrawal R. Exploring risk factors and perinatal outcomes of preterm birth in a tertiary care hospital: a comprehensive analysis. Cureus. 2024;16(2):e53673.